THE AMERICAN TIME: 1942 - 1945

The precise date of the arrival of the first U.S. troops is

not clear. Sam Caseley's god-daughters, who used to live in Redland but

who visited the Caseleys regularly, remember the arrival vividly. At

the back of the Caseleys' cottage was an emergency water tank. The

young teenagers used to swim there in the evenings. One evening they

were suddenly surrounded by strange men speaking with American accents.

These were the very first U.S. personnel. Since the girls were out

swimming in the evening, then it was clearly warm and light enough for

them: I therefore reckon that this was probably late May or early June.

According to Vera Wilson's researches the U.S. units were as follows

(the dates are partly mine):

U.S. units at Frenchay Park Hospital

1. ? May 1942 - ? Sept 1942: 152nd Station Hospital

2. 4th Sept 1942 - 26th Oct 1942: 77th Evacuation Hospital

3. 27th Oct 1942 - 12th Nov 1942: 2nd Evacuation Hospital

4. 13th Nov 1942 - 16th May 1944: 298th General Hospital

5. 17th May 1944 - 4th Aug 1944: 100th General Hospital History

6. 5th Aug 1944 - 5th Jul 1945: 117th General Hospital

7. 6th Jul 1945 - 16th Aug 1945: 52nd General Hospital

A site devoted to US medical services in Europe in WW2 can be found at US Medical Research Centre. It's well worth a visit, and is a remarkable example of dedicated research by a Belgian and a Briton.

As can be seen, the first three units each didn't stay for very long. Their presence was, however vital to the eventual functioning of the hospital. Just how vital was revealed to me in 1992 when some photocopied pages arrived from the States. They came from a book called 'Medicine under Canvas', which seems to be the official history of the 77th U.S. Evacuation Hospital- the very one which arrived in Frenchay in September 1942 - and deal with their period of occupation. I know no more of the book than that, but its pages make fascinating reading. They are worth quoting in their entirety:

... American Hospital in Salisbury. This organization, better known as the Harvard Unit, was composed of American personnel who volunteered long prior to Pearl Harbor, and was set up in well equipped buildings on the outskirts of the city. The nurses were quartered in one wing of the hospital with nurses of the 38th Evac. and 48th Surgical Units. In spite of the somewhat crowded conditions, there was ample compensation in the comfortable recreation hut with radio, reading-room and snack kitchen. The warm welcome of Lt. Bernice Wilbur and her gracious hospitality were important factors in making the stay here enjoyable. The nurses were also granted passes to London and the nearby towns. No actual hospital work was done but early morning calisthenics, gas mask drill and lectures were part of the regime.

On September 4, a detail of seventy-five officers and men left Tidworth and traveled by train to Frenchay Park, on the edge of Bristol, to take over a new hospital plant still under construction there. This institution was being built by the people of Bristol as a crippled children's hospital, but as the need for hospitals for American troops increased, had been taken over by an American station hospital. The buildings were one-storey brick and tile construction with flat roofs, and were well dispersed among the trees of a flat, park-like area. Several of the buildings, including living quarters, wards, operating ward and administration building, had been completed, and the advance detail now set to work cleaning up the buildings and installing the British equipment as it was brought in. Within a few days the remainder of the officers and men, and all the nurses arrived. The officers and men considered such things as a good roof, a bed, and a warm building strictly as luxuries, and with the boost in morale attendant upon getting out of the cold, wet tents, the work of cleaning up went forward rapidly. American rations were now available and the food, prepared in the large, modern kitchen was, on the whole, excellent in comparison with the fare at Tidworth.

A follow-up of the interviews on the 'Orcades' was made, ratings commensurate with a man's ability and training were given, and the personnel assigned to the various departments accordingly. Within a short time the hospital was ready for operation and patients were received from the American troops in the surrounding area and from the U.S. 2nd General Hospital at Oxford. Since this was the first time the unit had operated as a hospital, it served as a trial run, and each day several valuable lessons were learned by all departments of the organization. The receiving department, which at first was thrown into confusion by more than one ambulance load of patients at a time, soon became efficient enough to unload a fairly large convoy of ambulances while the drivers were having chow. The mess department soon learned that at each meal a few of the professional personnel would be delayed by duties and that ambulance and truck drivers must be fed at irregular hours.

A concentrated, basic training program was given to the officers and men who had joined the unit too late to receive this training at Fort Leonard Wood, and each morning the small group of 'rookies' went through their ritual of close order drill, hand salute by the numbers, and gas mask drill. On the wards, the newly assigned men were taught how to read a thermometer, give a bed bath, make beds, take blood pressure and pulse, and serve meals. Officers and nurses served as instructors in these classes, and the practical application of these principles went on under the surveillance of the previously trained technicians. In the operating room, new men were taught sterile technique. Although there was little actual surgical work, teams were organized and the fundamentals of plaster of Paris casts and splints, and the handling of sterile surgical instruments, sutures, dressings, and other equipment were taught. This training was done entirely with British equipment and it was repeatedly necessary to point out that American instruments and supplies were different. The electricians became acquainted with the intricacies of British wiring and fixtures, and since there were no G.I. tools, they spent about fifty dollars of their own money to buy tools from the local ironmongers so that defective sockets, fuses, lamps, and switches could be repaired. The utilities section operated the boilers which supplied steam heat to some of the buildings, and hauled coal for the small stoves in the other buildings. The untried plumbing system created many problems. Since this was the first working experience with the 52-series of medical records, it was necessary for the registrar's section to hold frequent conferences with the medical officers concerning the proper execution of these forms.

From the officers of the surgical service, several specialist teams were organized, and the members of these teams attended postgraduate courses in their particular field at various hospitals and medical schools in England. Maj. Howard Snyder, Capt. Wendell Grosjean, and Capt. Harwin Brown attended a course in thoracic surgery; Capt. Joseph Lalich and Capt. Tom R. Hamilton received special training in blood transfusion methods and the treatment of shock: Capt. John Bowser and Lt. James E. McConchie went to X-ray school; and Capt. Francis A. Carmichael and Lt. Robert Forsythe attended the course in neurosurgery at Oxford. The latter two officers came home steeped in the traditions of Oxford and wearing, with their class A uniforms, the 'old school ties' of the college to which they had been attached.

The headquarters and finance section began to function more smoothly, and on September 10 a paymaster was located and the unit was paid for the first time in about seven weeks. With money in their pockets, the extracurricular activities of the 77th people began to increase. Trips to London on 48 hour pass were fairly numerous, and attendance at the local dances, pubs, and theaters increased considerably. Many acquaintances and friendships were established with the citizens of Bristol and its outlying villages of Staple Hill and Fishponds, some of which are still maintained by correspondence. The Lord Mayor of the City of Bristol, resplendent in silk hat and the other regalia of his office, visited the hospital with his retinue and had lunch at the officers' and nurses' mess. As more and more of the members of the unit were invited into the homes of the people of the community, there was less misunderstanding between them. In spite of the fact that these people were on strict food rationing, they generously shared their meager stores with the American soldiers and apologized because they had so little to offer. Soon, nearly every man had a favorite pub, a skittle league, or a girl in the neighborhood to occupy his off-duty hours. A party was given by the enlisted men in one of the larger vacant buildings on the hospital grounds, affording an opportunity to show the English girls the 'American way' of throwing a party. The affair was very well attended, and although the girls did not care for the American beer which they maintained was too cold, they were amazed by the huge amounts of sandwiches, candy, and peanuts so generously proffered them. Several nurses helped with the decorations and refreshments, and worked in the powder room. The officers and nurses shared the same mess hall and recreation rooms and in off-duty hours a constrained group of nurses would congregate in one end of the recreation hall while an equally constrained and austere group of doctors kept to their end of the room. An attempt to organize an officers' club failed chiefly because at that early stage no need for organized recreation was felt. The first ration of British NAAFI spirits was distributed equally, but left an excess of nearly two cases of gin. A dance had been planned, and in the punch, extremely well concealed in the various fruit juices, were the two cases of gin. After an hour or so of freely imbibing this delicious and healthful punch, the most haughty became jovial, rank lost its privileges, and informality prevailed. Many experienced difficulty in navigating the fifty yards or so of concrete walk to their quarters in the blackout, and several unkind things were said about construction companies who would leave open ditches on the grounds. After this ice-breaking episode, congeniality became more evident in the mess and recreation halls. Occasional social functions by both civilian and military groups of the British in the Bristol area were attended by groups of officers and nurses who were always impressed by the stiff formality of these affairs.

Under the management of Capt. Howard Dukes, the first American PX ration was made available. An excellent variety of chocolate bars, peanuts, American canned beer and cigarettes could be purchased in plentiful amounts. At this time officers and nurses were issued clothing ration coupons, and shops in the city were besieged with requests for woolen sweaters, Scottish plaids, English tweeds, and other well known British products.

The first big consignment of mail came on about September 12th and, although most of it was from four to six weeks old, it was no less welcome.

Whilst at Frenchay Park three medical administrative corps officers, Lt. Leslie B. Williams, Lt. Randall O. Thompson and Lt. Oscar E. Milnor, and two medical corps officers. Lt. Leonard J. Haas and Lt. Edward J. Keeney, joined the unit.

On the large commons bordering the hospital grounds, a baseball diamond and a football field were laid out and the local citizenry always turned out in force to see these American games played. On occasions the Americans were given the opportunity to see a game of cricket.

English air defense officials gave several instructive lectures and demonstrations to he entire group on such subjects as bomb disposal, use of air-raid shelters, and rescue and first aid to bombing casualties. Usually the lecturer had had considerable experience during the air blitzes of the summer and early fall of 1941. Representatives of the National Fire Service also gave lectures and demonstrations on the latest methods of fire fighting, especially concerning defense against attack with incendiary bombs. Soon the 77th had a crew of fire-fighters who were quite adept with the 'sturdy stirrup pump' and the other apparatus.

Before leaving the States, an effort was made to collect and assemble all items of equipment needed to operate a hospital. A Table of Basic Allowances listed every piece of equipment, and by consulting it, one could see at a glance how many hospital ward tents or how many pen points were considered necessary. Few samples of this equipment were available during the training period, and most of it had been assembled at the port of embarkation by Lt. Robert Newman. At the time the organization left the States approximately eighty to ninety per cent of the equipment had been procured, assembled and labeled with the code number of the organization for shipping on a freighter. On its arrival in England this equipment was stored in a medical supply depot where it was to he held until the unit was ready to use it. Another evacuation hospital needed its equipment before the 77th did however, and, since they were only about 30 per cent equipped, an exchange of needed articles was arranged. This made it imperative that the 77th supply department procure the missing seventy per cent in short order

This proved to be a very difficult task. Supply depots were dispersed all over England, and the entire supply organization was still in a state of development which made for confusion in attempting to locate a particular item. All roads appeared the same, and there were no signs on any highways to guide an unacquainted traveler. So completely were the English people indoctrinated in security regulations at this time, because of a feared German invasion of England, that one could stop at a crossroad and ask a native for directions and receive nothing more than a disinterested, 'I don't know' for a reply. It was necessary for an officer to accompany the triplicate or quintuplicate copies of requisitions for equipment, and since the organization had only one of its six allotted medical administrative officers assigned to the supply department, several doctors unacquainted with supply procedure were pressed into service. Many and anguished were their cries when a long days journey in the cold, damp English weather without food had failed to net any of the elusive supplies. Only too frequently they would ferret out a supply depot in an obscure warehouse or chocolate factory to he told that the particular item in question had been transferred to another depot in an entirely different part of England, or that they were then awaiting a new shipment from the States, the last shipment having fallen prey to a Nazi submarine in the Atlantic. Notable among the minor items of scarcity was toilet paper. None of the American variety was available, but after considerable adroit negotiation, a limited supply of the British product was procured. This proved to be of a quality similar to the paper on which the 'pulp' magazines are printed, but each section was carefully printed with a crown and the trite statement that this was 'His Majesty's Government Property'.

It soon became apparent that having ninety percent of the equipment did not necessarily mean that the hospital would he ninety percent efficient. For instance, without the shock-proof tube cables, which weighed only a few pounds and constituted only one item on the list, the X-ray department's other 9,243 pounds of equipment were entirely useless. Such problems as this could not possibly be recognized by the supply officer himself, since he was a member of the quartermaster corps, and had had no previous experience in matters medical. This necessitated frequent conferences with the chiefs of the various services to determine which items were absolutely essential even if they had to be purchased on the open market, and which ones could be substituted by makeshift improvisations.

Since no electro-surgical unit was included in the Tables of Basic Allowances, and none could be obtained through army channels, a collection was taken up from the officers and one was purchased on the open market for four hundred dollars.

During the latter half of October, 1942, rumors of a big move began to be buzzed about camp. The officers of the medical department, strictly on a hunch, had purchased textbooks on tropical medicine, and lectures on the subject were given to the enlisted men. Supplies poured in, extra winter clothing was issued, and gas-protective ointment distributed. Pup-tents were issued to the nurses and they were given instructions and demonstrations on pitching them. Two newspaper correspondents, Frank Kluckhohn of the New York Times, and William W. White of the New York Herald-Tribune, were attached to the organization. These preparations led to discussions on Russia's climate, the price of Persian rugs, 'Soirs de Paris', the Belgian Congo, and many other parts of the world. When Lt. Robert Newman was again sent off, this time to Liverpool to assemble the equipment and see that it was properly crated and marked, the air of mild anticipation became one of feverish expectancy. The natural desire for new experiences and more tangible contact with the war was tempered with a reluctance to leave this garrison type of life at Frenchay Park, which seemed an ideal spot to 'sweat out' the war.

The personnel was divided into A and B groups, each capable of operating as a separate unit complete with surgeons, nurses, technicians, and clerical personnel. All baggage was marked with a design of three bars and a circle, and packing began. Many found that the souvenirs they had collected while at Frenchay had swollen their baggage to the point of nearly bursting the seams of the barracks bags, and, to add to these difficulties, six cans of C-ration, several bars of D-ration, and odd cans of fruit juice, corned beef, cheese and sardines were issued. On October 26 personnel from the 2nd Evacuation Hospital arrived to take over the remaining patients and the hospital.

The first group left on the evening of October 27 and the second was scheduled to go on October 29. All personnel were restricted to the immediate area on these last two days, but on the evening of the 30th, when the enlisted men's roster was checked, only about half the detachment could be found. As on the previous evening, the restrictions had been disregarded, and many of the men were in the pubs of the neighborhood (chiefly Stan's) engaged in impromptu farewell parties. Fortunately, the detachment commander proved to be quite lenient when a final roll call shortly before departure revealed everyone present.

The junior grade officers of the second movement had never been advised as to the exact time of departure, and were told to remain in their quarters until transportation ...

The above, apart from some included

photographs, is all that I received on the copied pages. I wonder how

many examples of the complete book 'Medicine under Canvas' still exist

in the world?

[ In late 1999 I found on the

web site of the US Library of Congress that 'Medicine Under Canvas' had

been published in 1949 (196p with illustrations, maps etc). It is

described as 'A war journal of the 77th Evacuation Hospital'. No author

is given. Robert Gerlach, who sent the pages to me, never replied to my

letters].

For the next couple of weeks the hospital was occupied by the 2nd

Evacuation Hospital which was affiliated with St Luke's Hospital New

York City and drew some of its staff from there.

On November 13th 1942 the first of the more permanent units arrived in

the shape of the 298th General Hospital. The 298th was an amalgam of

two other units, one of which was also called the 298th. This one came

from the University of Michigan and consisted of medical and nursing

personnel from the University; it had been started in 1940 by a

far-seeing member of the University medical staff. However, it

consisted only of University doctors and nurses - it had no cooks,

typists, orderlies or any of the many other skills needed to run a

hospital. In consequence, when the need came, the staff were sent off

to Camp Joseph T Robinson in Little Rock, Arkansas, where another

General Hospital was stationed. This was the 214th and consisted mainly

of all the personnel lacking in the 298th, but had virtually no doctors

or nurses of its own. In fact it consisted of about three hundred

enlisted men and only four officers. The Michigan people arrived on

June 28th and the combined hospital took their name. On October 14th

they all moved to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey where they stayed until

embarkation to England and eventual arrival at Frenchay Park Hospital.

(A vivid personal account, by one of the 214th, of the event before and

after arrival is given later).

|

|

|

||

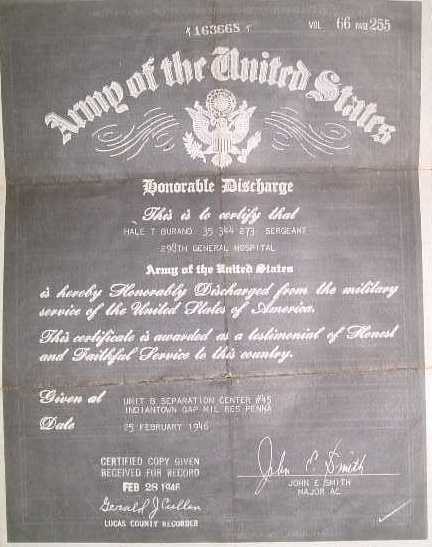

Tom Burand; his 298th. shoulder insignia; part of his discharge paper. Tom was a clerk in the 298th. He married a Bristol girl. After the War they returned to the US but, after a few years, went back to Bristol. Pictures taken December 2004 and November 2005.

Vera Wilson extracted details of the stay of the 298th from the 'secret' Annual Reports that they had sent to Washington and which she obtained from the U.S. National Archives during the preparation of her 1981 booklet. To quote:

On the 13th November, 1942, the 298th General Hospital, a unit affiliated with the University of Michigan, arrived and took over the base until 16th May,1944. During that period the hospital was visited by Queen Mary, and later by the comedian, Bob Hope.

Shortly after the arrival of the 298th General Hospital Unit, encouragement was given to women of the nearby village to train as a volunteer corps to help in the hospital. The British Red Cross recruited and identified these volunteers and a training programme was devised in which senior American Army doctors and nurses and the American Red Cross participated. Thirteen women received their qualifying certificates in May and a further twenty-four in July, enabling them to work in various parts of the hospital including the Library and handicraft section. They also coped with flower arrangements and accompanied patients to social functions.

Frenchay continued to serve as a training centre for newly-arrived Medical Units, and a great deal of attention was paid to training programmes and to inter-Allied co-operation and goodwill. American doctors attended professional and scientific meetings with their British and Commonwealth colleagues in Bristol, Bath, Oxford and London.

During the summer two American Army doctors, a neurosurgeon and a thoracic surgeon, took over the practice of two British civilian doctors to allow them a well-earned and much needed rest, and four American Medical Officers attended a three-day conference designed to demonstrate the plaster casts which were used by the British in the transportation of fracture cases.

The land chosen for the Frenchay Emergency Hospital site had been a beautiful stretch of parkland with clumps of trees and small ponds, but as the result of the building programmes, much of Frenchay Park was scarred and heaped with rubble.

The 298th General Hospital staff assisted by civilians planned a market garden and planted trees, shrubs, flowers and grass around buildings and along side improved paths and roadways. Mrs Herbert Thomas, Director of the W.V.S., Bristol, had a great deal to do with the landscaping and beautification of the grounds. She gave much time and imagination to the transformation, and the result was a striking profusion of colour at all seasons of the year. The daffodils enjoyed in March she planted personally, and chrysanthemums raised at home and transplanted to Frenchay gave pleasure in the autumn. Unfortunately an unusually dry season followed, killing the arboritae and chinese junipers, but lilac, forsythia and other shrubs survived.

Around about this time the Bristol Art Museum loaned pictures, on an exchange basis, which were accepted and hung in residential hutments, lounges and mess rooms. An aerial view of Frenchay, taken in 1943, shows the parallel rows of wards in the foreground: officers' and nurses' quarters, headquarters, special hospital departments and the motor pool in the centre background, with the company area and enlisted mens' quarters in the upper right of the picture.

Aerial view around 1943 from the University of Michigan archives, corresponding to the map below .

The 298th found the hospital too small

for their needs; plans were therefore drawn up and the facilities

extended. The original E.M.S. hospital, according to Jimmy Yule, a

youth in the village at the time and eventually the hospital's General

Foreman, had been built by a London firm. The extension work was

carried out by a local firm called Harvey Simmons. They constructed the

following:

12 General Wards, 1 Isolation Ward, 3 Officers' Wards, 1 Officers'

Dining Room and Recreation Area, 2 Stores, 1 Mental Ward, 1 Patients'

Recreation Ward, 1 Twin Operating Theatre, 1 Water Tower, 1 Cook House,

1 Fire Station, 1 Guard House, 1 Gas Defence Stores, 1 Post Exchange, 1

Dental Clinic, 1 Operating Wing Boiler House, 1 Chapel, 1 ENT Clinic, 1

Nurses' Mess, 1 Office and Quarter Master's Building, 3 Venereal

Disease Wards, 1 Boiler House, 1 Sick-call Clinic, 1 Enlisted Mens'

Dining Room and Recreation Area, 1 Pumping Station, 1 Officers' Wash

Area, 6 Junior Officers' Living Quarters, 5 Sergeants' Living Huts, 1

Sergeants' Club Room, 1 Sergeants' Ablutions, 3 Enlisted Mens'

Latrines, 3 Enlisted Mens' Bath Areas, 3 Enlisted Mens' Ablutions, 34

Enlisted Mens' Living Huts, 8 Air Raid Shelters.

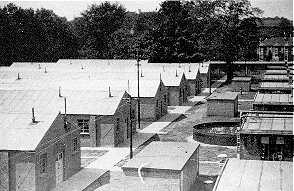

Back ramp wards built 1943. Note lack of covered walkway. The semi-circular construction is an emergency water tank. The small brick buildings are coal bunkers for the stoves of both ramps of wards.

In the 1990s the hospital funded a complete copy of the 298th's Annual Reports from the U.S. National Archives. In those reports was a sketch map of the hospital in 1943.

Map showing Frenchay Hospitals in 1943 taken from US Archives and redrawn by the Dept of Medical Illustration. The Bristol Corporation Sanatorium is on the right, the American Hospital bottom left with living quarters above. A guard house is strategically placed at the crossroads between the American Hospital and the Sanatorium - where the nurses were! (NB The original was hand drawn). NOTE: The image size is deliberately large so that the building names are reasonably legible. Please read in conjunction with the 'Buildings' chapter.

In summer 2014 a previously unknown 1943 map came

to light. It was drawn up by a firm of Bristol architects and is much

more detailed than the one above. Click here

for the map.

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

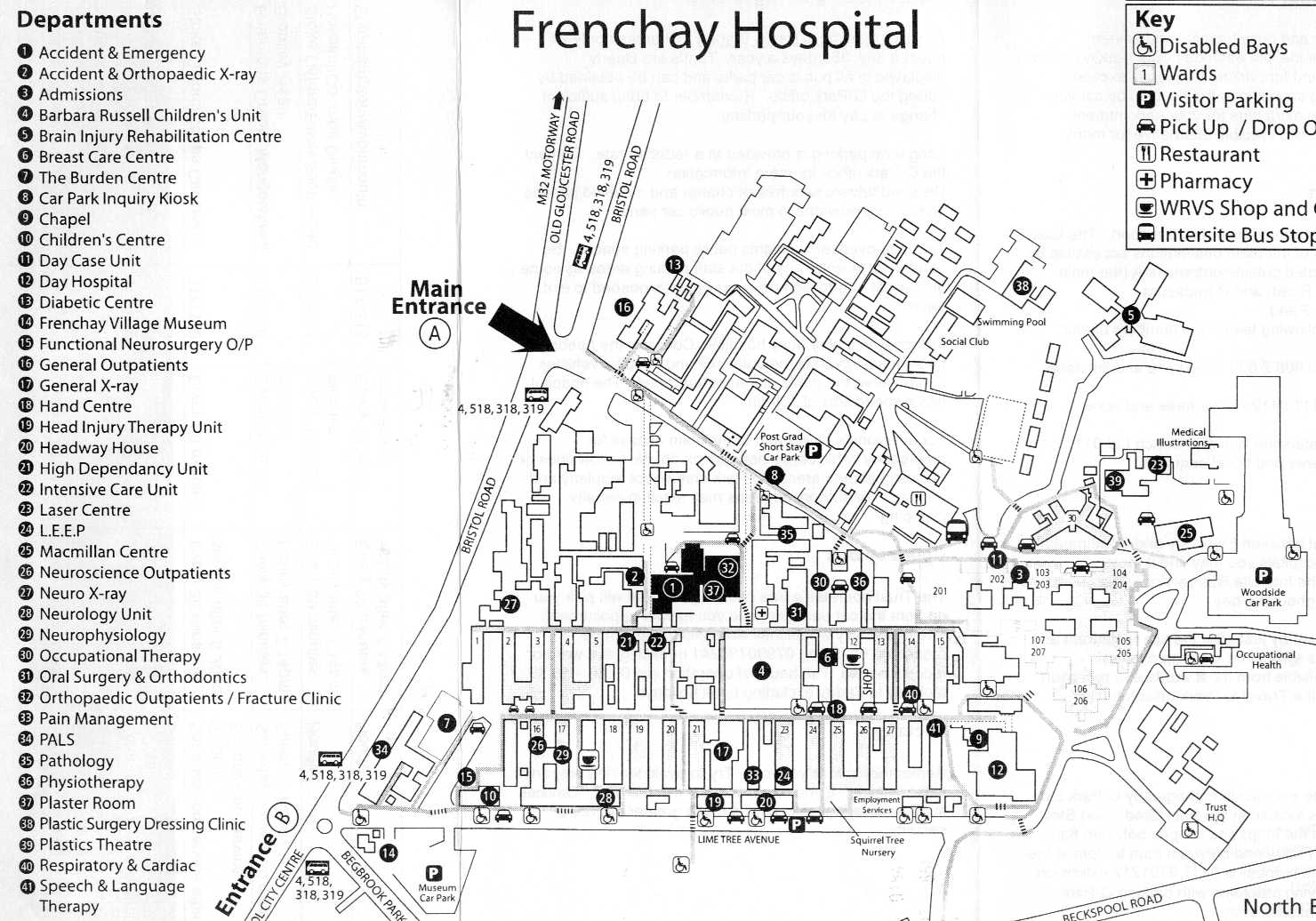

By comparison with the 1943 map, a map of the hospital in 2006 shows

how much things changed over the 60+ intervening years. Within a few

more years much of the old hospital will be demolished and facilities

moved to the new complex at Southmead. Click on map for a high

resolution version.

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

When the building programme was completed the hospital was reorganised

to allow for medical specialisation. These sections were: General

Surgery, Neurosurgery, Orthopaedic Surgery, Thoracic Surgery,

Ophthalmology, Otolaryngology, Urology, Maxillofacial and Plastic

Surgery, Anaesthesia and Operating Theatres, Physical Therapy.

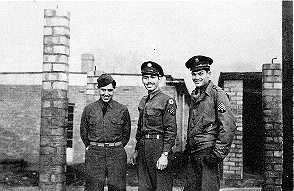

GIs standing in front of the columns of the covered walkway being built in front of the back ramp wards.

Photograph showing the covered walkway. Circa 1950s.

The 298th left Frenchay a few weeks before D-Day in 1944. [They were sent for a few weeks to Colwyn

Bay in North Wales for fitness and other special training, after which

they spent 2-3 weeks at Brockley Combe transit camp, South of Bristol, prior to

embarkation to Normandy in July 1944]. They were followed

at Frenchay for a short time by the 100th General Hospital. The 100th

was then sent to France in August 1944 and was set up in a Normandy cow

pasture for the next seven weeks.

On August 5th the 100th were replaced at Frenchay by the 117th General

who stayed until early July 1945. By the time the 117th arrived, the

Battle of Normandy was well and truly under way; casualties arrived all

the time. Vera Wilson's extract of the Annual reports indicates:

This unit was later commended for the efficient procedures they had developed for admitting and evacuating large numbers of patients. It was estimated by officers and enlisted men, who participated in the receiving operations, that a train-load of some 300 patients could be completely admitted, including documentation, from the railway station to the wards, in approximately two hours.

During the period 5th August to 31st December 1944, a total of 4,954 patients were discharged from Frenchay, either back to duty, to another hospital for further observation and treatment, to rehabilitation centres or to the Zone of Interior.

During that period 1,084 servicemen were decorated. Special ceremonies were held, sometimes in the wards and operating theatres. A total of 114 Oak Leaf clusters, 2 Silver Stars and many Purple Heart ribbons and medals were awarded.

John Penny gives some insight to the activities in and around the hospital at that time:

During June 1944 Fortress bombers were arriving regularly at Station 803 as the Americans called Filton aerodrome, and disgorging batches of crisp, attractive-looking American nurses. They were destined to serve in No. 94? General Hospital in Bristol. A huge medical support operation was under way, backing up the D-Day bridgeheads, with hospital and convalescent units spread throughout south Gloucestershire. By the end of 1944 a continual stream of Dakotas was bringing wounded personnel into Filton from France, whilst other Dakotas brought in precious cargoes of plasma and medicines to supply the hospitals.

(From

'Wings over Gloucestershire' by John Rennison, Piccadilly Publishing,

Woodchester, Stroud, 1988)

John Penny describes the arrangement of the local Home Guard units

associated with the airfield as follows:

The 18th Bn. was a special battalion with its H.Q. at Filton Airfield, along with 13th Bn. Unlike most other local battalions the 18th did not have posts in various districts (just two in the Aircraft Factory) but mainly provided special services for other units. Its H.Q. Company was for signals and bomb disposal;'W' Company was at Filton Works N& W; 'X' Company was at Filton Works S &E; 'Y' Company were Fire fighters (?Decoy Sites?); and 'Z' Company were the Regimental Police.

There was clearly a close relationship between the hospital and Filton airfield. It is perhaps for this reason that a special ceremony took place on October 20th 1944 when Lieutenant Colonel Denholm, the Commanding Officer of the 117th, was presented with a small Union Flag as a token of friendship from the 18th Battalion of the Bristol Home Guards. The flag, the base of which was made from the stonework blitzed from the Houses of Parliament, was presented by Lieutenant C.O. Worth, Commanding Officer of the 18th Battalion. A British band furnished the music whilst a platoon of uniformed British Home Guard officers and men, as well as enlisted men from the 117th, stood in formation.

Other ceremonies also took place, not all of them so clearly related to the War. Vera Wilson's chapter on the U.S. times concludes:

On another occasion, a wedding took place in the hospital chapel. Second Lieutenant Geraldine A. Hake, a member of the 117th General Hospital nursing staff, was married to Second Lieutenant Frederick A. Clay, whose permanent station was in Iceland. Captain F. Tolle, Protestant Chaplain, performed the ceremony and Lieutenant Colonel Denholm gave the bride away.

On 6th July, 1945, the 52nd General Hospital took over from the 117th General Hospital. This unit had been overseas for over two years and had welcomed V.E. Day with relief, but they had coped with so many badly wounded and mentally harassed young men that their rejoicing could not be exuberant - they were just thankful it was all over and that they had been able to help a great many servicemen, and women, on the road to recovery. Their stay at Frenchay Hospital was of short duration and on 17th August, 1945, they were transferred to Everleigh Manor, near Tidworth, and about two weeks later embarked for America.

Frenchay Hospital was handed over to the British on the 17th August, and so ended a brief chapter in its history, but the links forged between the Americans and the British during those war years have remained strong and the years 1942-1945 will take their place in American-British history.

After the Americans left, a small detachment of British Army personnel were stationed at the hospital, mainly to protect the buildings and equipment. In spite of this, most of the domestic and some of the medical equipment 'disappeared', never to be seen again. This is touched on in the next chapter.