PERSONAL MEMORIES OF THE WARTIME

Over the years many people have given me their recollections

of the War period. Some were local people, some were children in the

Sanatorium and quite a few were Americans, including one who was a

patient. I think their memories are worth recording; a few follow:

Audrey Curry, village child - letter to the Evening Post, 1992:

Like May Hill I have happy memories of the Americans during their stay at Frenchay Hospital. I was a child living in Frenchay village, and I remember how kind they were. When they arrived they didn't understand our money and we were often requested to go shopping with them, making sure they got the right change. Our reward was gifts of Palmolive soap, chocolate and gum. How Mum welcomed the soap! There was one (a school teacher back home) who would borrow a horse and cart on a Saturday. Off we would go around the country lanes, all laughing and enjoying ourselves. At Christmas we were invited to parties in the hospital. I remember having apple tart with sticks of gum standing up in it. At the end of the war we had celebrations, and a sports day on Frenchay Common when the Americans gave us lovely books as prizes. Mum, Dad, my three brothers and I all won races receiving prizes. What a good time was had by all!

Christmas 1944. Sister Hunt, children and US nurses.

[In 1992 this picture appeared in the Bristol Evening Post (21st August). A cutting of it was sent to me with the names of several people written in. Sister Hunt is holding the horse, David Bartlett and Michael Hennesy are sitting on it. Nurse Hill is holding a child with Nurse Hancock next to her and Sister Farrell just behind. Nurse Howell and Sister Hampton are further to the right. The child with the US cap on the far right is Tony Leonard. During a lecture on the history of the hospital in Jan 2000, I showed the above picture. A member of the audience stood up and said he was the 4th child from the right in the front row! He is Donald Lear and he was an inpatient in the Sanatorium from Oct 1943 to Feb 1944. The picture is therefore Christmas 1943 and not 1944.]

Chaplain George Crofoot (far left) and colleagues with Bristol children from bombed homes invited to the Bristol Hippodrome, January 1943. The other officers are, L-R: Lt Col Oscar T Kirksey (CO 298th), Lt Col Walter G Maddock (next CO 298th) and Maj Robert R Shaw. After the war, Maj Shaw specialised in thoracic surgery in Dallas and was one of the surgeons who tried to save President Kennedy's life. When this picture was published in the Evening Post in 1992, several of the now grown-up children recognised themselves.

Another picture of the two Lt Cols can be seen here.

[Maj Robert Shaw did not operate on President Kennedy; however he did twice operate on, and save the life of, the other victim, Governor John Connally. Major, later Professor, Shaw died in Dallas in December 1992 after a stroke. He was aged 87.]

The Lord Mayor (and Santa Claus) visiting the children in the Sanatorium at Christmas 1943 or 1944. The patient is Doreen Dunton who died from TB at Frenchay on the 13th July 1945, aged 13.

Hilda Fry (neé Baker), British stenographer at Frenchay during the War - letter to the author:

I was interested to note that you have the address of Clifford Kiehn, the Plastic Surgeon, whom I remember very well. I did, in fact, work with him a good deal, as being one of the only stenographers guaranteed not to faint at the sight of blood -one poor girl managed it when merely asked to don a gown and mask! I often accompanied him on his ward rounds, making notes of his comments as he examined his patients. This, you must remember, was in the days before personal tape-recorders, and everything was done by stenographers, operation reports, autopsy reports and progress reports.

I also did some private secretarial work for Clifford Kiehn who was carrying out what were then innovative treatments in skin grafting and the use of sulpha drugs, and he asked me if I would assist him in his preparation of a paper for the American Medical Journal. This I was delighted to do.

In passing, I must mention that, while some may consider the programme M.A.S.H to be somewhat over the top, I never ceased to be amazed at the capacity for some of those surgeons with whom I worked during the war to be completely legless at night and then back in the theatre the next morning performing the most delicate feats of surgery.

When I was called up for National Service, and directed to work at Frenchay Hospital, my first assignment was as secretary to the Chief of Laboratory Service, one Lt. Col. Francis Bayless, pathologist, of the 298th General Hospital and with whom I kept in touch after he was invalided home. The last time I heard from him was in November 1945, when he was Director of the Sixth Service Command Laboratory in Chicago, and itching to get out of uniform and back into civilian life.

I was instrumental in designing and setting up the filing system of their laboratory records, all of which was quite new to me, having previously been a secretary for the Scholastic Trading Company, then in Bridge Street, Bristol. One of my first pieces of dictation included a reference to 'polymorphonuclear leucocytes' (no abbreviations in those days). I must have blanched visibly, as the next day I found on my desk a large medical dictionary and several very useful reference books which not only enabled me to find the correct spelling of all these strange terms, but also get a rough idea of what it was all about. So started my interest in things medical in which I was encouraged by Col. Bayless who encouraged me also to do blood counts and prepare sections of tissue for microscopic examination, and offered me employment in the U.S.A.- which, owing to my family circumstances at the time, did not happen.

Your reference to the 'Secret Report' I also found interesting, since I had a hand in editing and typing many of the official reports 'to go back to Washington'. During my time in the laboratory Col. Bayless became aware of my interest in drawing and I was asked to do certain anatomical illustrations for inclusion in his reports. It is somewhat daunting to think that these crude efforts (now, as a semi-professional, I realize how bad they were) may still be lying around in the archives available for anyone to see.

Although I had hoped to continue in my laboratory work for the remainder of the war, it was not to be, for with the increase of casualties in the hospital, and since the records of the laboratory were running smoothly, I was transferred to the Registrar's Department where I had to organize an ever-growing pool of civilian stenographers and where life became more hectic by the day.

Little did we realize when an officer burst into the room and yelled 'It's today!', and ringed all the calendars in red (yes, D-Day!) just how hectic life would become with the incessant flow of patients with all the attendant paper work, not the least of which was organizing convoys of patients to be repatriated to the U.S.

I remember the British liaison sergeant you mention. There was also a civilian liaison officer, a Mr Culverhouse, and a permanent Clerk of Works, a Mr Forster (whose daughter, Zoe, was engaged to a sergeant in the laboratory - whether they eventually married I do not know). As far as I remember, Mr Forster remained at Frenchay Hospital for the duration of the war.

I was much amused by your statement that '...British troops were there to prevent bits of equipment "disappearing".' I clearly remember the day when the American troops moved out and the British troops took over. The detachment, as I recall, was commanded by a Captain Catt, and I was the only civilian stenographer retained to assist with preparing the inventory of items left by the U.S. troops. It was amazing how not only domestic equipment but other hospital supplies had suddenly become very much depleted and seemed to have vanished into thin air.

During my years at Frenchay with the U.S. troops I had never known it anything but spick and span in spite of the poor condition of some of the buildings. Everything was always scrupulously clean and the 'trash details' never idle. Within a few days of the British troops taking over all that changed, with the grounds and ramps littered with the inevitable bits of paper, cigarette ends, etc.

I am not surprised at the comment 'the gardens and grass verges were unkempt and rubble had been dumped in large mounds'. These conditions would certainly not have obtained during the American 'occupation', but things rapidly deteriorated after they left.

I eventually said goodbye to Frenchay Hospital, and although I attempted to return there when it had been converted into a British hospital, my application was rejected. I worked for a time at the B.R.I., and eventually wound up on the administrative staff of the then South West Regional Hospital Board.

Mrs Fry included some photographs, some of which have found their way into this book. She also sent the Menu for Thanksgiving Day, 1944, giving a complete roster of the members of the 117th General Hospital. This is now in the Monica Britton Hall at Frenchay. She goes on:

All the food eaten in the mess halls was imported from America, with the exception of a few locally grown vegetables. Even the milk was imported, being either condensed or evaporated, since the local produce was not considered suitable for human consumption, even supposing there had been enough of it to feed the vast numbers to be catered for. The civilian office staff ate in the Officers' Mess, and fared extremely well- individual helpings of steak often being equivalent to a British family's ration for a week.

'Mac' Goldfinch, a 19 year old U.S. soldier and patient at Frenchay - on a walk with the author in September 1989:

Mr William 'Mac' Goldfinch - patient in the hospital from December 1944 - April 1945, admitted Christmas Eve 1944 after the 'Battle of the Bulge' in the Ardennes. He says he cannot remember the ward number he was on but there were about fifty patients in each ward and all of them on his particular ward had developed frozen feet during the course of the Battle of the Bulge. They were all going to be shipped back to the States but they called a specialist over from Boston who managed to treat them locally. Many of the patients had gangrene of the toes and it was so common that the amputation was undertaken on the wards, the bed was screened off, sterile equipment and sheets were brought in and the amputation performed there and then without sending the patient to the operating theatre. Individual patients never knew when they were due for the chop. 'They' would make a morning round and then a decision would be made that a digit had to be amputated. Mr Goldfinch refused surgery when his turn came; he said he wanted medication and he was therefore given some of the rare Penicillin, 20,000 units into his leg four times a day. He never had his amputation of his toe, which in many other patients had been followed by further digital amputations and eventually amputation of the foot. He never had any of that and he still has an intact limb. In order to preserve the feet, patients' digits or feet were left exposed. It was very cold weather and the surgical and nursing staff often worked with Parkas on.

When Mr Goldfinch was eventually discharged from the surgical ward to go to the recuperation ward he walked past his ward's chart room[likely later to be one of the sister's offices]. The doctor who wanted to do the amputation but who eventually gave him the Penicillin, had subsequently developed a considerable antagonism to Mr Goldfinch. He was sitting working near on a chart [set of clinical notes] and Mr Goldfinch, on crutches as he walked past the door, said to him, 'Well Captain, I am leaving this ward on my own two feet', whereupon the doctor threw the chart at him!

After his discharge from the surgical ward and whilst the was recuperating he ran the hospital theatre which, he told me as we walked past it, is now the Recreation Hall; he used to put on the movie shows there. There also used to be psychiatric patients here and one of them used to come in and sit in the front row of the cinema and wait for the show to start and, as soon as the show started, he'd get up and walk out! He would do this for every show. When Mr Goldfinch was a patient there he was nineteen years old. He turned nineteen on 29th November 1944 in a fox-hole in the Ardennes and then was subsequently injured on December 19th, 1944 and eventually admitted to Frenchay Hospital on Christmas Eve 1944. Apparently the hospital was also used as the centre for pregnant U.S. female military personnel prior to shipment back to the States. The psychiatric element was large and, according to Mr Goldfinch, all patients admitted from combat went through a complete review by all departments prior to their discharge, this including going through the dental department and the psychiatric department; every department of the hospital was apparently involved in the patient's workup prior to discharge.

Incidentally 'Mac' came to Britain as an eighteen year old; he landed in Scotland in mid 1944 and was eventually sent by train to a camp at Lyme Regis in Dorset. He was given night duty and therefore had his days free. On his first day he tried to buy a proper photo frame for the photo of his girlfriend, back in the States, which she had given him just before he left. This was in a simple little cardboard studio frame and he wanted a better one. He was eventually sent to a shop at 50 Broad Street in Lyme Regis and went in and asked if they could make or supply a leather frame for him, whereupon the owner said 'Yank, we haven't had any leather since the beginning of the war but if you leave me the photograph I'll try to make something better than you've got'. The owner measured his pocket and the photograph, and took the photograph so that everything fitted nicely. At about that time a bell rang upstairs in the shop and he said 'Oh, that's Amy, it's time for tea. Would you care to come and join us for tea?'. So on his first day this eighteen year old, homesick, scared-to-death American was taken upstairs and had tea; he went back every day for the three weeks that he was stationed in Lyme Regis and had tea with the people. He became extremely friendly with them. He was subsequently shipped off to Europe where he was injured, as described earlier, and eventually came back to Frenchay Hospital where he wrote to the people in Lyme Regis. Amy immediately came to visit him carrying a bag of goodies and he has stayed friends with the family ever since. They have been over to the States, their children have been over to the States, and the American children have been over to Britain; it has been a life-long friendship all as a result of going to find a photo frame back in 1944.

One of the other things Mr Goldfinch had to do while he was

recuperating was to stand guard. This we eventually ascertained was at

the Bristol entrance, where the old lodge house still exists and where

Mr Mustoe used to live. It was Mr Mustoe who used to come out at 5

o'clock in the morning and bring the young Americans, who were guarding

the gate, cups of hot tea. I told 'Mac' that Mr Mustoe was still alive,

whereupon the old veteran immediately wrote a little 'thank you for the

tea' note on his visiting card for me to hand on to Mr Mustoe. This I

subsequently did.

['Mac' Goldfinch

made contact in Dec 1995. He was suffering from Parkinson's disease. He

had seen a documentary on NBC TV in the States which included a lengthy

piece about pioneering surgery for the disease carried out at Frenchay

Hospital! He felt that his life had come a full circle. Similar surgery

was available nearer home and this was undertaken in January 1996 with

a successful outcome. 'Mac' also pointed out that "Amy" was in fact

"Ada".]

Lois Monroe was attached to the American Red Cross. At the time of the

1992 fiftieth anniversary celebrations she produced a wonderful

compilation of memories, photos and 'where are they now' in the form of

a booklet. It included the following:

WE MET THE DOWAGER QUEEN MARY

It was July 1943, Frenchay Park. Our Chaplain Crofoot was sometimes asked to take the pulpit on Sunday evenings in neighboring churches. On one such occasion he preached in the village of Chipping Sodbury where the Dowager Queen Mary stayed during part of the war. She was in the congregation and asked to have him presented to her after the service. Chaplain Crofoot did the gentlemanly thing and invited Queen Mary to visit our hospital. Thus it came about that a number of us got to meet her.

Nothing in our training had prepared us for this. None of us had ever been presented at Court. Some knew people who had, and contributed what they could remember. But that was really no help. This was not Court. This was not even a formal situation. The Queen was coming to see a U.S.Army hospital in action. She would want to see us at work, everyone agreed.

The question arose should American officers (nurses) curtsey? It was decided that as we were not Subjects, this would not be appropriate. It was concluded that those in charge of a ward or department should do as they did in any military inspection, step forward as soon as the inspecting party entered, and salute, giving their name and rank.

There were other questions of protocol to be worked out as well. Naturally we would want to offer Her Majesty some refreshment before she left the post. However the neighbors who had been advising us warned that, in these austere times, the Queen would not condone refreshments being prepared especially for her. If it were customary for us 'to have tea in the middle of the afternoon', they assured us that she would be happy to join us. But we should not, nor should we, expect the Queen to contravene wartime public policy.

The Chief Nurse's Office was assigned to make it look as though it were a matter of custom for us to stop work every afternoon and drink tea. She must plan a scene in which a group of decoys were to be assembled in the Nurses' Recreation Hall and give the impression of having their customary afternoon tea. The Royal party would be asked to join in with the others, and all would be well.

Yet there remained one more detail to be arranged. Our British friends said that it was required that we prepare a special restroom for the Queen's visit. Medical minds at the hospital assumed that this was due to the gracious lady being elderly. The handling of this matter was also delegated to the Chief Nurse's Office. A very special polishing and decorating job was done on the room in the Reception Building that Her Majesty would be invited to use. Miss Shaeffer was left to work it all out.

At last, the Administration felt that everything had been thought of and arranged for. The Post had undergone the spit-and-polish job of its life. Patients with chest colds and other ignominious ailments were transferred to the back ramp, and battle casualties were put up front where they would be easily accessible. There was not a wrinkle in a bed, nor an unpressed uniform anywhere. The Chiefs of the Departments were lined up in front of the Reception area with Col. Kirksey, Captain Shaeffer and Chaplain Crofoot in front. The Queen and her entourage rolled up, were ceremoniously assisted from their cars, and the introductions were made. There was a pause while the Queen, arrayed as we had always seen her pictured - in light lavender coat, the famous hat and plume, the tightly furled umbrella and the concave heeled 'opera slippers' surveyed the scene- and Miss Shaeffer sighed. Nudged by the Colonel, she stepped forward and asked, 'Your Majesty, would you care to step into the ladies' room before we begin the tour?' Her answer was a surprised but nonchalant, 'Thank you. No.'

And so, with only a vague look of incredulity, the Colonel led off the tour. Actually, nothing went quite as it had been planned that afternoon. Certain doors were opened for the Royal look, and others, it was understood, were to be left closed. But this Lady was an experienced hand at inspections, for her umbrella gestured more than once toward the doors that had been passed by. She did not want to disappoint the men in the back wards and went in and spoke to them; never mind why they were where they were.

The last stop before tea was at the Red Cross Recreation Hall where pictures were taken. From there the party made its way to the Nurses Recreation Hall where the appointed were waiting by the small but laden table to lift cup to lip and munch on dainty sandwich. As the party entered the room and surveyed the group, the Queen's Gentleman-in-Waiting took one horrified look, dashed forward, and in a very audible stage whisper exclaimed, 'Ladies, please - no one eats before the Queen!' Trying not to look too crestfallen, the nurses put their cups down and sandwiches back on plates. The Royal party were invited to 'Please join us in a cup of tea.' Graciously our guest accepted, and had a chair drawn up to the small serving table. About a dozen others were obliged to follow suit and do likewise. To paraphrase Churchill, never had so many been crowded into a space intended for so few.

At several stops throughout the post, the Colonel insisted that the Queen be given renewed opportunities to visit the ladies' room. Each time with unfailing aplomb, her answer was the same. 'Thank you. No.'

But somehow the tour seemed to go off moderately well in spite of the inner agonies of the Administrative Staff. The Queen apparently enjoyed herself and her victory over the attempts to coerce her into the ladies' room. The staff enjoyed the privilege of having had tea with the Queen, and the rest of us basked in the warm glow of the reflected glory. It was only months later that we learned that a specially prepared private rest room must be readied whenever any Royalty, young or old paid a visit.

When all was over and the Royal party had departed, we all set to with vigor to get our days' work done - each in the back of his mind probably planning how he would tell about this to his grandchildren.

Many years later at a reunion of the 298th in the States I met Chaplain Crofoot's assistant. He told me that, after her first visit, Queen Mary came on a private visit most weeks and stood in silence for a few moments in the Chapel (later turned into Medical Records and then part of the Path Lab). She did this on many occasions and also apparently often went to Bristol Docks, near Bristol Bridge, and looked at the swans.

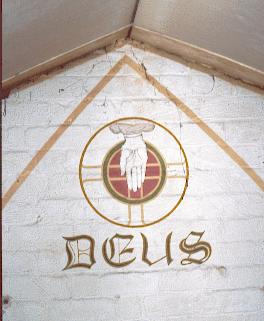

The Chapel, Christmas 1943, where Chaplain Crofoot officiated and Queen Mary came privately most weeks during the war. A later Chaplain's paintings above the altar are still there above the present false ceiling.

In April 2005 I was sent a copy of the opening ceremony of the chapel in March 1943. This came from the grand-daughter of Col Kirksey, the C.O. of the 298th who had found this site on the internet. The document can be seen at Chapel.

[The later painting, done by the 117th General Hospital, post June 1944]

[ Still there in 2001]

Christmas celebrations at the end, or just after, the War.

Many other memories have been related to me, but the most poignant I could only read - I never met the author. He was Lott Broaddus Bloomfield, a corporal who worked in the Sick and Wounded Office. He was a great poker player. After the War he worked for Exxon. He died in the late eighties from emphysema. The War had clearly made a great impression on him. In 1945 he recorded his memories of his time with the 298th. He clearly also had a way with words:

After four years in the Army of the United States, during which time I underwent countless changes of habitude, I find myself today situated on the outskirts of Liége, Belgium. In a manner retrospective of the progressive chain of events leading up to our presence in Liége, I should like to give you a brief summary of my life during these past four years. In so doing, I shall endeavor to relate only the essential facts, dealing basically with the facts and figures and eliminating as much as possible the frills and fancies.

In the early summer of 1942 the 214th General Hospital was situated on 10th Arkansas Avenue in Camp Robinson, about six miles out from the city of Little Rock. Major Watson, whose home is in Montana, was in command, and the Group of some three hundred enlisted men had only three other officers. Most oft his group had come down from Camp Grant, Illinois in June 1941. Just one day before they arrived in Little Rock, I was inducted in the Army and took the oath of allegiance on June 16, 1941, in Houston, Texas. My first day in uniform was in Fort Bliss at El Paso, Texas. Three weeks later I was transferred to Camp Grant where I completed thirteen weeks training. During the second week in October I travelled to Little Rock where I was joined up with the 214th.

It was in July of 1942 when things really started happening. Some of the nation's leading doctors from the University of Michigan Hospital came to Little Rock and joined up with the outfit. In an entirely new role, the former 214th changed its number, and was to become known in the future as the 298th General Hospital.

On October 12th the 298th entrained for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, a port of embarkation. We stayed there just five days. On the eve of the 19th we pulled out of Kilmer. The short journey by train ended when we reached the banks of East River. We crossed the river by ferry and in the distance we caught a glimpse of the Statue of Liberty and, above the shore line, the phantom looking skyscrapers of greater New York peered at us through the darkness. In the harbor our ship was awaiting our arrival and, along with some five thousand other troops, we boarded her that night. It was dawn before we sailed, and it was on the morning of October 20th that a throng of men stood aft on the decks of the 'Mariposa' looking back at the 'Grand Old Lady', some seeing her for the last time. Before the war, the 'Mariposa', an 18,000 ton vessel, had been a luxury liner between San Francisco and Honolulu. She was now one of the gray ghosts of the Atlantic;just one of the many great ships that took American boys off to war. Her luxurious quarters had been altered for troop accommodations and our section aft on one of the upper decks had once been a spacious ball room. It was now converted into a maze of iron hammocks, four deep.

For the first two days at sea we had a flotilla of destroyers as our escort to safeguard against submarines, for at this stage of the war, the sub menace was rampant. There was a strange difference in the way we felt about the voyage when, on the morning of the third day, the destroyers and also the two dirigibles, which had been our guardian angels, turned back and our proud old skipper took over full responsibility of getting his sea queen safely through these darkening waters of that treacherous Atlantic.

Just before noon on the fifth day, the inevitable happened, and this time it was no 'dry run'. The ship's sirens screamed out that feared warning! Submarines! My hair stood on end with excitement and fear as the ship's guns boomed out in defiance. The big five inch gun on the lower deck was pouring volley after volley into our churning wake. Depth charges were set off all about the ship and in our excitement, fear was almost forgotten. Our blood was tingling in a tantrum as rumors ran wildly through the ship's quarters. After fifteen minutes of waiting and anxious expectation, the all clear signal was given and we all drew a sigh of relief. Although it was never really substantiated, we were told by some of the ship's crew that we had been very lucky because we had just run squarely through a whole nest of subs.

The remainder of our voyage was without incident and without marine company, friendly or otherwise, in as much as we know. That is, until the morning of the last day when we sighted a British destroyer which had been sent out to meet us. The destroyer stayed with us for the final lap of our trip. Just off the Irish coast we came upon a ships' graveyard. Ghostly looking derelicts lay scattered all over the bay while, off to our left, a huge British carrier, complete with its planes girded for battle, steamed ocean ward and a long with her were two heavy cruisers and five destroyers.

On the 28th of October we sailed around the hood of northern Ireland, came down through the Irish Sea, and docked at Liverpool at six o'clock in the afternoon. We debarked at 10pm. What a vivid and lasting impression! There she stood! England! England, in all her historical splendor! Battered, but not beaten! As we marched along the streets of Liverpool we were all but spellbound by the reality of it all. Even in war, this was England, yes, you could feel it. A typical fog enshrouded the city, but even as she lay there quiet and still, draped in a wartime blackout, you could still make out the trim lines of her towering buildings and majestic cathedrals stamped indelibly upon a graven sky. There was no mistaking of that 'limey' talk we heard in the streets as we encountered small crowds along the way. Though there was no display of emotion in the welcome we received by these people, we did not for once doubt their sincerity and we were truly made to feel that our presence was appreciated and welcome. Throughout the entirety of my stay in England, I found later, good opinions formed early were not to be changed, and England and her people were everything I had hoped they would be.

We didn't get to stay long in Liverpool. We marched to a trolley line where we boarded an odd looking double-deck trolley car. Our trip on the trolley was brief and we soon came to a railroad station where we entrained for Birmingham. Birmingham is the Detroit of England, and in this vast and scattered metropolis we stayed only a fortnight. We were stationed in a district called the Phoese Farm Estate where we were quartered in two storey brick buildings which were only partially completed. There were British troops stationed at the same place, so on the very first night we joined up with them and visited the local 'pub', the 'Trees'. We drank bitter ale and beer, which, though much different from American beers, was quite good. We sang English folk songs with the 'Tommies', and they in turn sang some American ditties with us.

Early in November we moved on to Bristol where we stayed some twenty months. About six miles from the heart of the city, in a district called Frenchay Park, we set up a very attractive hospital. It was a choice site with beautiful surroundings. Just back of our place there was an English children's hospital, and off to the left, was the parish church with a graveyard in back of it and a large open lawn (called 'Commons' by the British) in front. The English sometimes played cricket on the Commons and we played softball there.

In the evenings, when we were free from our work and from the wants and sufferings of the sick and wounded men at the hospital, we spent our time getting acquainted with the English people and their customs.

There were dances on three nights of every week in the various church recreational buildings in the suburbs around Frenchay. The ones that our fellows attended regularly were St Mary's and St John's in Fishponds, and Paige Hall in Kingswood. It was at St Mary's in December of 1942 that I met the Vickery girls; there were three of them, Joan, Betty and Peggy. After the dance I walked home with them. At their home, on (22) Berkeley Road, I met Mr and Mrs Vickery and Mary, the youngest of their five daughters. Eileen, the eldest daughter, was living in London with her two year old daughter, 'Pippa'. Eileen's husband was an officer in the Royal Navy. It was in the spring of1943 before I met these members of the family; then I saw quite a lot of them again at Christmas time of that same year. Mr and Mrs Docherty were the family's best friends. I used to get quite a kick out of Mr Doc, and I liked to hear him talk; and he, in turn, was obliging, because he did a lot of it. He was a jolly fine fellow with a marvelous personality. Having lived in London for some time his speech still had that 'cockney' air about it. Mrs Doc was always of good humor; very quiet in her manners she was and had the sweetest of dispositions, indeed, a truly refined English woman she was. The Dochertys had one son, Charles, who was with the RAF in Canada.

In the many times that I visited in the home of the Vickerys in the following months, I came to know them and to regard them as real friends. Mr Vickery was employed by the government and worked in the postal service. He had served as an officer in the last war. A quiet and modest man, well past his fiftieth year, but a man who had worn his years well, and a man who had lived a happy life. He was highly respected in his neighborhood and his cheerful disposition and congenial air made him an ideal father for this family of five lively young ladies. Mrs Vickery was a lovable soul, and though I never told her, I was particularly fond of the way she called me 'Lott', with what I would call, definitely, an English accent. She reminded me in many ways of my own mother; perhaps because all mothers of larger families have similar problems. Mrs Vickery managed her household well, and there was no doubt that she had become devoted to her domestic attachments.

With Mr Vickery I had many long chats and we used to joke about putting in a 'fish and chips' shop or a 'honky tonk' in Texas after the war. He had a very keen sense of humor. I remember once when he afforded all of us a laugh with his sharp wit. Don Martin and I had called at his home to ask him to join us in a beer at the 'Spotted Cow'.

When we arrived, Mr Vickery was alone, and he at first hesitated on leaving without telling his wife or one of his daughters where he was going. I suggested that he might leave a note, so he did. I don't know whether my Texas talk had influenced him or not, but Don and I laughed until our sides ached when he showed us the message he had written. It went like this: 'Folks, see you in the morning. Have gone honky-tonkying with Don and Lott'. The three of us had a bicycle each, and after leaving the Spotted Cowwe cycled down through Fishponds to another place more in the country, a little place called 'The Tavern'. The Tavern was situated on Blackberry Hill, a beautiful countryside overlooking the creek that ran through the glen down past an old snuff mill where the ancient water wheel was still grinding away though its energy was now leashed only to the wind. In earlier days Mr Vickery had made his home among these beautiful surroundings.

Mr Vickery didn't have any sons, but he treated me as though I may have been his own boy. I was given a room in their home and was allowed to come and go as freely as I chose. Lamar Tullos [Joe], my lifelong friend, will vouch for the things I have told you in regards to this English family. Even yet in the letters I receive from Mr Vickery, he always asks about Joe. Those reunions with Joe which I was fortunate to enjoy while we were both stationed in England meant a lot to me. I shall never forget how strange it seemed to see him that first time. He had somehow found where I was situated and had called me from Bristol. At the time he called I wasn't around and the sergeant at information had given me the message. It had been many long months since I had seen anyone from anywhere near home;I almost dropped when I saw that familiar grin as Lamar crawled out of that jeep in front of the office that day in Frenchay. I had told the Vickerys that I was expecting an old friend from home and they insisted that I bring him over to the house the very minute he arrived. So, after Joe and I had a long talk and I had introduced him to all the fellows I worked with and others among the hospital personnel, he and I went to call on the Vickerys. They received Joe in a manner that paralleled the hospitality of our finest southern hosts and they added much to make our meeting a pleasant occasion. These happy hours that triumphed the happiness of the joyous days of my boyhood and early youth were not full and many, but they added much to my efforts to sympathetically understand the problems of the men at the hospital who, like ourselves, were a long way from their loved ones, and were now lying broken and suffering.

I hadn't really known how awful it was going to make me feel when I saw that first group of battle casualties. I was helping out in the receiving office on the morning of 24 December 1942 when they came in, nearly a hundred in all, casualties from the African campaign. They were all badly wounded; some with arms missing; twelve had either one leg or both gone. It was a pitiful sight, and these guys who had suffered such physical losses were so brave and resolute about their injuries that it swelled your pride to see these traditionally red-blooded American lads facing their misfortune with a determined (though possibly a little forced) smile. I choked back my own feelings, and with a hearty smile I turned to one fair haired boy, he had just turned nineteen, to offer him a cigarette. He had one arm and both legs missing. He looked up and with a broad grin, taking the cigarette, he said 'thanks, buddy', and then looking more carefully at the cigarette taking notice of the brand, he added enthusiastically, 'Hey Camels, too! Boy that's a treat after smoking them damn limey cigarettes on the boat'. It was my job to get all the information from him needed for our files. In this included information concerning his nearest of kin. This person was the kid's mother. His face lit up when he started telling me about her, and after he had given me her name and address, he continued, 'Guess Mom is going to feel pretty bad when she sees me in this shape; but she shouldn't feel that way, because I don't. I'll bet a lot of those ...', and here he faltered as he turned to look at me. How utterly I failed that boy then, for as he looked into my eyes he saw the tears that were coming there, and he cried. Later that day I cursed myself for being so soft, though I could not have been otherwise, for never before had I such as I witnessed there that day. I went back on the wards that evening to try to help cheer up some of those boys because the next day was Christmas.

Never again did I give way to my feelings as I saw thousands of wounded men later. There were times, however, on several occasions after when I was deeply stirred. I remember on one occasion when Bob Hope and Frances Langford were visiting the hospital there in Frenchay. They had given a brief show on the grounds and Miss Langford was visiting in one of the wards where we had some badly burned cases. She stopped by the bed in which there was a fellow who had been terribly burned. Nearly all the flesh from his face was gone, both ears were burned off, and he was completely blind. This creature asked her to sing for him. She sat down on the side of his bed and in a beautiful voice she began singing 'Irresistible You'. How helplessly pitiful, and how heart grating the sight when charred tears began to fill those lifeless sockets. Miss Langford was almost overcome with emotion, but she finished the song. It was the last time she sang that day.

Patients continued to come in increasing numbers and the hospital personnel worked diligently in the coming months. Eventually, though I often doubt if it is an accomplishment, we came to where we could cope with even the most delicate of situations without the slightest chance of having the patient know how we felt in regards to his suffering. It must have been a strain though, because by the following June, when I was granted seven days leave, I was sorely tired and indeed happy to get away for a while.

There were five of us in all; Felix Lopez and Jimmie Donohue from California, Mike Magooch from Cleveland, Ohio, and Lavon Lynch from Tulsa, Oklahoma. We travelled by train, going first to London where we spent only a day. From there we proceeded to Edinburgh, Scotland, which I still contend, must be one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Princes Street is said to have no equal for its beauty in any country. Situated high on a hillside overlooking Princes Street stands the famous Edinburgh Castle which we went through during our visit there. We had a wonderful time in Edinburgh, and that old proverb about the Scotch people being tight with their money was again proved false. Never have I been treated better by anyone. The people were both friendly and generous as they welcomed us into their country, often refusing to accept payment for the things we saw to buy. Perhaps I became a little more prejudiced after several Scotsmen informed me that my name was Scotch. It came from a warring tribe among the Saxons who settled in northern Scotland.

The 298th was scheduled to be of the first hospitals in France after the forthcoming allied invasion of the continent of Europe. We had known that for some time.

Talk of invasion increased and the great day seemed imminent. In June 1944 we left Bristol and headed west for a spot in Wales known as Colwyn Bay. It is a beautifully situated city at the foothills of a mountain overlooking the bay. Here we had a full program of physical training, taking long hikes through the hills and valleys and we had refresher courses in drill, tent pitching and field life in general. All began to look healthy and tanned after a month of this life and we were now all set for our next assignment. Before going to our debarking point we went back to Bristol, this time on the opposite side of the city about eight miles out in a place called Brockley Coombe. During the few days that we stayed there our training program, which we started in Colwyn Bay, was continued. We were allowed to go into Bristol in the evenings, or if we chose, to Weston-super-Mare in the opposite direction on the sea. For me, it was almost like getting to go home again, for I went back to visit my good friend, Arthur Vickery, and his family. They said they were happy to see me again and pleased to see me looking so well.

Late one afternoon in the early days of July we were called into formation and, having been on the alert for three days, we were already packed, left Brockley Coombe that evening and headed for Plymouth. We stayed in Plymouth a period of five days before going aboard a liberty ship in the harbor there. We sailed on the morning of the 15th of July and landed on Omaha beach on the 16th. Again the voyage was exciting, even more so than the first time, because air activity was at its highest level about now and our troops were still fighting the battle of Normandy. What a sight of death and devastation the beach was! Pillboxes along the coast line had been knocked out by bombs from our planes and from the heavy fire of our battleships;there were half-sunken ships all up and down the bay; and floating debris of all description filled the briny, death-claiming waters of the channel. As we marched further inland upon going ashore that afternoon we saw further evidence of the terrific battle that was fought there.

When at last we stopped marching at midnight we had come within twelve miles of our troops' front lines and even closer to the heavy artillery that was throwing tons of steel into the enemy's lines. We bedded down in a big field which the engineers had cleared of mines and booby traps. Very few of us were able to sleep; most of us lay awake listening to the roar of the big guns and the resonant echoes of this incessant pounding. The nurses with the unit had already gone on into Cherbourg by truck that night, a distance of some forty miles. On the following morning trucks were sent for us and we headed for Cherbourg. En route we passed through Montebourg, Carentan, Bricquebec, and Ste Mère Eglise, names that will long be remembered for the death, hunger and destruction suffered there.

When we arrived in Cherbourg the city was almost vacant. Most of the civilian population had left for safer refuge; but a few of the hardier people and scores of scavengers were still there to give this place the air of an early boom town in western United States. Cherbourg had fallen only two weeks hence and enemy snipers still lurked in the city. The people all looked dirty and hungry and the streets were filthy. We selected for our quarters a huge marine building which had formerly been used by German officers for a headquarters. They must have left in a rush because the place was littered with personal letters, unused rifle cartridges, machine gun clips and many other articles that ordinarily would not have been left behind. On the day following our arrival there we went down to the hospital grounds two blocks away. The plot covered several acres and the hospital itself was an enormous thing. It had formerly been a French Naval Hospital of notable repute. During German occupation of Cherbourg the enemy had taken over. It was in the vicinity of the hospital that our troops encountered the last bit of enemy resistance. The stench of death still hung about the place when we arrived there, and after a brief search by some of our men, they found a shallow grave in one of the gardens in the hospital grounds that harbored over fifty dead, mostly all German soldiers. It was a sickening experience, and even up to the day we left that place I could imagine that smell still prevailed. Slightly less apprehensive after months of experience, we tackled the big job of cleaning the hospital and making conditions livable. It was an extremely distasteful and difficult task for there was no fresh water, no sewer system, and already we had patients to care for. We were the first General Hospital to start operating on the continent.

Our stay in Cherbourg was one not easy to forget. We put in many extra hours during the period of four months that we were there. In this time we handled and cared for over ten thousand patients. Even so, we had some time of our own and we spent that time going swimming at the beach, sightseeing around the old forts, and walking about the streets of this war-torn French city. There were a lot of accidents and deaths among the soldiers and civilians around Cherbourg. Hardly a day passed without the hospital receiving anywhere from one to fifty such cases. Our morgue was always filled, mostly with cases that were dead on arrival. Little children that had been playing in the fields stepped on old mines left by the Germans and were blown to bits. Some soldiers were killed by snipers in town, some were poisoned by drink, and still others were killed by booby traps and trick gadgets left by the enemy.

News came one day that our troops had liberated the greater part of Belgium and that spearheads had already plunged into Germany. Then on October 28th we left Cherbourg and headed for Liége, Belgium. It took us four and a half days to reach there by train because we were held up in several places to allow ammunition and food trains to pass. We were two days in getting to Paris. I was surprised to see how, opposite in comparison to London, this great city had been spared from great damage by the war. It was the first time I had ever seen Paris, and though we saw very little of the city proper, it was thrilling to see this magnificent city of the world as she lifted herself from the yoke of oppression and stood now gleaming in all her true beauty and splendor. We spent a whole day in Paris and even in this short time I came under the spell which her beauty creates. I have been thinking of going back there for a visit ever since we came to Liége, but here it is today, a late day in July 1945, and I have not been able as yet to get back to Paris. Probably I won't either, for our job in Europe is almost finished and we are waiting to get sent back to the United States. Before we leave I would like to tell you something of our experiences in Liége.

When we arrived on the first day of November last year the Germans were directing buzz bombs over this area. At that time only a few of them fell in this area because their targets were Brussels and Antwerp, two other Belgian cities. These deadly missiles made a very spectacular picture as they raced madly through the sky. The jet exhaust from those V1s was a fiery red, especially at night. They travelled at a low altitude in a direct path at a terrific speed, and the sound of the motor which seemed to follow at some distance, was much like that of an aeroplane, only much louder, more harsh and almost deafening. We were able after always to distinguish this sound from any other. It was not until mid-December when at last the Germans made Liége and the surrounding area targets for their fantastic flying bomb. It was a terrifying experience during the following three months as the enemy continued this onslaught, sending thousands of V1s to strike Liége. Of the seven U.S. General Hospitals, three received direct hits, one getting hit twice. Several casualties resulted each time. We were lucky, because we had many very near misses, but not one ever landed in the hospital area. We lost one enlisted man killed during the entire siege. Once, while in town, two of our boys bad the living daylights scared out of them when one came screaming down only a block away. They were thrown off their feet by the impact, but escaped serious injury. This was not so, however, for the seventeen civilians and eight American soldiers whose bodies were cleared from the wreckage that afternoon.

Our hospital was crowded with casualties resulting from V1s and we took in civilians as well as soldiers. I have not yet seen the figures revealing the number of deaths incurred in Liége by buzz bombs during those three months, but it must have been several hundred, perhaps thousands. Though we were pretty excited during the Belgian Bulge, which was possibly the enemy's greatest and certainly their last threat to upset allied plans of winning the war, I cannot say that we were ever in immediate danger of being captured or overrun by the enemy. Batteries were set up around the hospital as near as was allowed by the provisions in the Geneva Convention and we were given detailed instructions in just what to do if the Germans did come. One armored spearhead reached the opposite banks of the Meuse River just on the outskirts of Liége, and several paratroopers were captured in the city, but even while the enemy's advance seemed to be threatening our position, a large counter-attack by our forces was already developing and the Huns were doomed to hopeless defeat.

I have purposely refrained from describing some incidents that I witnessed simply because I want to forget these things that standout vividly in memory. But in order not to stir your curiosity and to make my report complete, I shall at least make mention of the greater part of those tragic incidents now; an innocent child five years old shot through the heart by a bullet that was meant for a soldier; a feeble old woman blown into a thousand pieces by a land mine; almost a hundred school children killed by one buzz bomb while they were attending classes; plane crashes in mid-air; a Fort exploding while in flight; an ammunition and oil dump hit by an enemy bomb. Yes, all of these things I have seen but, somehow, even harder to forget was watching a brave man die. I had come to know him quite well in the frequent visits I had with him on the ward in the hospital at Cherbourg. He was a veteran combat soldier, hardened to the war, having been twice wounded before in the Sicily and African campaigns. He was in the first wave of the invasion troops and had been hit by machine gun fire on the beaches at Normandy. He had shown me pictures of his wife and his two fine looking children, a boy and a girl. I think Ted knew he was going to die, but he never did allow himself to believe it, not even during those violent moments just before the end. I have wished often since that day that I had not been there when his cherished hopes faded with his last breath. How valiantly he had fought against unnumbered odds for the right to return to that little home he had struggled so hard to build. Except for his friends, those who were there that day, and that little wife and those two sweet children, Ted is now forgotten in this world of mortals, and his soul has gone to join those many other brave souls immortal whose bodies we have lain beneath the sod where now the poppies dwell.

We won't forget! We shall never forget! We cannot forget! But today, even while we are painfully conscious of the heartaches, the physical sufferings and the moral and mental strife that accompany war, we think upon these things and determine ourselves to help build a better tomorrow - where people live in happiness and in peace with one another in a world that knows no war![The widow of Lott Broaddus Bloomfield was contacted in Houston in January 1995. She was delighted to learn that her husband's memories have been included in the book. She later wrote to say that she and her husband had visited Bristol in 1985 and made contact with the Vickery daughters, Betty, Mary and Peggy. She requested copies of the book for her own four daughters and for Lamar Tullos. The Vickery sisters themselves made contact in February 1995. One of the sisters is married and lives in North Carolina. Two are in Bristol. Later, Betty Vickery corrected some inaccuracies in Lott's account; one, that her father was not an officer in WW1, but a sergeant, subsequently a Warrant Officer in the Reserves. Also she points out that the Docherty's son in Canada was Jack and not Charles.]

[In January 2002 Doug Booth, a US veteran, made contact. He had found the web site with the Hospital's history, and this had evoked many memories. The following is part of what he wrote to me.

"I am a native Virginian, born in Charlottesville, Va. Home of Thos. Jefferson`s University of Virginia and his Monticello home. That was a while back, July 4th. 1925 - I don't remember the traditional fireworks! I was quickly hauled into the army when I reached 18. I lived in the house I was born in until then. Shortly I was sent off to a camp in Oklahoma and trained as a mortar gunner in the infantry.

In early '44 I was sent to join the 79th. [Lorraine Cross] infantry div., 313th reg. as a replacement mortar gunner in a company. This was at a camp in Kansas. Soon we were headed for Boston, then Glasgow. We finally arrived at our new home on the grounds of Marbury Hall very near the small town of Northwich, Cheshire. I think that is correct. I believe it was not too far from Manchester. It was then April. We were settled in tents, no heat and no electric. There we continued to train and take long night marches. It was in Northwich that I had my first fish and chips with malt vinegar served in a piece on newspaper rolled up to fashion a cone to hold the food. It was great. I had some recently in my local town - just before Christmas - at a place named Penny Lane pub. It was just as good, maybe a little better served on a plate.

We embarked from Portsmouth, struggled ashore on Utah beach June 14th. '44. The landing craft didn't get in to the beach very close. The water was almost up to my neck. I did my best to hold the mortar and my sidearm above my head. We were not under fire then but by nightfall we were.

I was moved to the US army hospital at Frenchay Oct. 1st. 1944, after being wounded in eastern France. I left Frenchay in early `45 for the States. I really enjoyed the area once I was able to get around.

I can say that I was very grateful to be there . It was a great relief to leave the combat behind, come out of it mostly intact and alive even if it did mean taking some shrapnel. It would be hard for others not having been in the same fix to imagine the great sense of relief I felt.

We had at the hospital good food and plenty of it, good care, lots of free time and rest.

No one told us anything about the history of the hospital and I'm sure most like myself didn't ask. Looking back I think that was a shame. I didn't know that children were nearby on the grounds, as your history mentioned. The wards were more like barracks except the beds weren't double decked. There was a big coal fired stove in the middle. We had a radio, there was (almost always all the American big band and jazz recordings and the news. On December 15th. '44 I can remember the hurt we felt when the news of Glenn Miller missing over the Channel came on that radio.

One day probably, between Thanksgiving and Christmas, three or four of us pooled our resources and took off across the grounds to a pub. I think it was in a direction opposite the hospital entrance. We found a pub, wasn't very far, on a road that I would guess is now M4 going by the map on your web site. [actually, almost underneath an elevated part: JB]. Anyhow, we purchased a quart of rum, took it back to the hospital concealed. I'm assuming we had a pretty fair afternoon with that; we played card games, cribbage, and things like that, a lot.

The doctors let my arm heal, then opened it up almost from armpit to wrist to try to piece the ulnar nerve back together. The arm was in a cast for quite a while. I quickly became good friends with a captain there who was in the same division as myself, but another regiment. He was wounded in the same battle. We went into Bristol frequently. More on that another time if you care".]