From The Daily Telegraph for Saturday 4 September 2004

DEREK JOHNSON Talented half-miler who championed the cause

of athletes as their sport entered the era of professionalism

DEREK JOHNSON, who died on Monday aged 71, was one of the

finest half-milers in the 1950s, but earned wider fame as the

sharp-tongued creator of the International Athletes'

Association.

He caustically urged British athletes to defy Mrs Thatcher's

call for them to boycott the 1980 Olympics because of the

Russian invasion of Afghanistan, calling her "a fighting

cock who thought her success in the chicken run at home had

turned her feathers into armour". This provided

significant encouragement for the British athletes Steve

Ovett, Daley Thompson and Allan Wells, as well as Sebastian

Coe, the future MP, peer and secretary to William Hague as

Opposition leader, who went on to win gold medals at the

Moscow Games.

If the general public was surprised by Johnson's outburst, it

was only because it . had forgotten that he had once enjoyed

a reputation as the "Angry Young Man of Athletics".

Johnson clashed with team officials at the Melbourne Olympics

in 1956, because of their alleged meanness over pocket money

that nearly caused a strike. At the Empire Games in Cardiff

two years later, he was dropped from the 4 x 440 yards relay

to "prepare for the future". This provoked him to

write a letter saying that if officials were going to treat

athletes like performing monkeys they should be grateful for

the peanuts thrown at them, and that he would not run for

Britain again.

This led to the formation of the International Athletes' Club

which, under Johnson's leadership, did much to improve the

lot of athletes in that pre-professional era.

Johnson was to the fore in the successful campaign to stop

cigarette companies from sponsoring athletics a source of

personal satisfaction because his father had died of lung

cancer.

None of this, however, could overshadow the fact that Johnson

was a superb natural runner with a beautiful action, whose

ranking list range from sprints to crosscountry, hurdling and

steeplechase - is matched only by Sydney Wooderson and Ovett.

He won gold medals in the 880 yards and 4 x 440 yards relay

at the Empire Games in Vancouver in 1954. The next year he

ran the 880 yards in 1 minute 48.7 seconds, beating by half a

second the British record set by Wooderson in 1938.

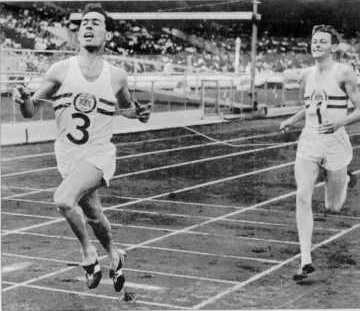

Johnson, left, defeating BS Howson over 880 yards in a record 1m 48s in

1955.

But he is best remembered for the final of the 800 metres at

Melbourne when he was beaten by a foot in a titanic battle up

the home straight into a head wind by Tom Courtney, an

American who was almost five inches taller.

Johnson had to change his tactics after having trouble with

his starting blocks. He stayed boxed in, hoping to find a gap

to take the lead near the finish; and when one opened up 70

metres from the tape he went through like a ferret after a

rabbit.

His strategy almost worked. He and his rival were side by

side until almost the last stride when Courtney took the lead

to win by a tenth of a second, but it was so close that he

turned to Johnson and asked, ""Who won?" '"You

did, Tom," the Briton replied.

When they met again for lunch a few days later, Johnson

greeted Courtney with the remark, "I've run that race a

thousand times since Monday, Tom, and beat you every time."

"Yeah," the American retorted, ""I've

done that too and, Derek, I just ate you up."

Derek James Neville Johnson was born at Chigwell, Essex, on

January 5 1933. He won national school titles while at East

Ham Grammar School, and his sensational 440 yards in 48.8

seconds at the AAA junior championships in 1950 marked him as

a potential international star.

He soon fulfilled this with AAA championship wins and a fourth place in the

European 800 metres in 1954, the same year that he won his two gold medals

at Vancouver in the Empire Games. He won a relay silver in the 1958 Empire,

but lost his gold in the European that year when the British team that won

was disqualified.

After doing National Service as a second lieutenant in the

East Surreys in Egypt, he had a fine athletics career for

Oxford while up at Lincoln College.

Johnson was game for anything. He ran his own computer

company, tried his hand at property redevelopment, played a

major part in the restructuring of British athletics and

promoted road races and athletics meetings, including the

highly successful Coca-Cola meetings at Crystal Palace; he

was also secretary of the AAA of England.

'"I am not a believer, but I had this God-given gift,"

he said. "I could sprint. I could handle any distance. I

just had this natural talent." What should have been

Johnson's greatest years were blighted by health problems.

He lost part of one season through tonsillitis and then, in

1959, far more seriously, he contracted tuberculosis.

He had just finished his medical studies at Oxford and was to

start work as a doctor* in London when he collapsed after

running his fastest 1,500 metres in Finland while already

infected with TB, which he had probably contracted in the

chest medical ward. Months later he fell ill on the plane

after his great victory, and spent the next six weeks in bed.

"'One lung was obliterated and the other two thirds

affected," he recalled.

"Two more weeks and I would have had it." He spent

six months in a sanatorium, then gave up medicine for

computers and athletics. Four years later he started running

again.

Turning up at the White City aged 30 he did such a fine time

that it gave him hope that he might make it to the Olympics

in 1964. But it was not to be. He survived TB but was

crippled by Achilles tendonitis, for which there was no cure

in those days.

He remained with the International Athletics' Club until it

wound up in the late 1980s as the sport moved into the

professional era; later he helped to draft the constitution

of the British Athletics Federation.

Johnson still ran the London Marathon in under three hours

aged 50. Although diagnosed with leukaemia seven years ago he

joined the Olympic torch party as it went through London this

year.

Derek Johnson was divorced from his first wife, Maria; he is

survived by his second wife, Lakkhana, and their daughter.

Copyright Daily Telegraph 2004

*Derek never actually qualified. He did preclinical training at Oxford and then went to the (then) London Hospital for clinical study. He told me that, after he had recovered from TB, he realised that he couldn't continue with both his medical training and athletics. He opted for athletics. Before, and during his EHGS time he lived with his extended family at 98 Rosebury Avenue, Manor Park.

Jim Briggs, former classmate

From The Times Thursday, 9 September, 2004

Derek Johnson

Runner who won a silver medal at the 1956 Olympics and then did much to

foster athletics in Britain

DEREK JOHNSON was one of the most talented, versatile and courageous track

athletes this country has produced. Two years after becoming the Empire

Games 880 yards champion, he took silver in the 800 metres at the 1956

Olympic Games in Melbourne.

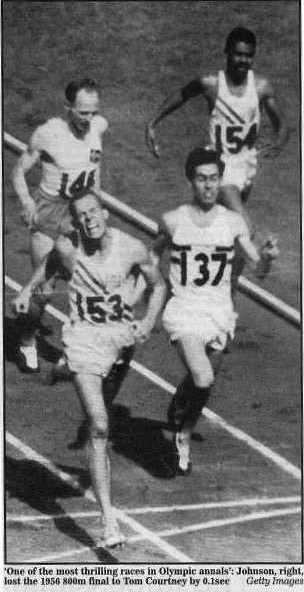

In his history of British athletics, Mel Watman declared that Johnson’s

battle with the bigger and stronger American Tom Courtney in the Olympic

final was “one of the most thrilling in Olympic annals, and Johnson was one

of the most heroic losers in athletics, timed in 1:47.8sec to Courtney’s

1:47.7sec.”

The anonymous athletics correspondent of The Times, a former Woodford Green

club-mate of Johnson, reported: “Johnson ran a race of superlative judgment

in a final which had everything a connoisseur could demand except a world

record. Johnson led Courtney for eight unbelievable strides towards the tape

before the American closed the gap and got home by two feet.”

Years later, writing for the Achilles Club, the former Oxford blue Johnson

recalled: “Perhaps the most apt commentary on Olympic finals in general was

an exchange between myself and Courtney in the Melbourne Olympic Village a

few days after. I greeted him with the remark: ‘I’ve run that race a

thousand times since, Tom, and beat you every time’. ‘Yeah,’ was the

excellent reply, ‘I’ve done that too and, Derek, I just ate you up’.”

Derek James Neville Johnson was born in Chigwell, Essex, in 1933. His mother

died during the birth. He soon became the best runner at East Ham Grammar

School; he ran the 880 yards in 2:01.2sec when he was 15. Two years later,

he made national headlines when he won the AAA Junior 440 yards, on a far

from helpful track, in the precocious time of 48.8sec.

Just over 5ft 9in and around 10st 9lb, Johnson had a long, flowing stride

and the capacity to remain relaxed when under pressure. Interviewed by the

sports historian David Thurlow this year, he said, “Though I am not at all

religious, I had what could, I suppose, be called this God-given gift to

handle nearly any distance, a natural talent.”

After National Service in Egypt as a second lieutenant with the East

Surreys, he read medicine at Lincoln College, Oxford, where he enjoyed a

fine athletics career. As OUAC secretary, he supervised the preparation of

the track for Roger Bannister’s sub-four-minute mile.

He began to work in the chest clinic of a London hospital where, he

believed, he contracted the tuberculosis which, with one lung obliterated

and the other two-thirds affected, obliged him to languish in a Midhurst

clinic during 1959.

On recovery, he quit medicine for computers. There seemed little chance of

his running again. Yet in 1963, to his own astonishment, Johnson returned to

the White City track near his London home and ran 1:50sec to finish fourth

in a top-class invitation 800 metres. Only Achilles tendonitis wrecked his

dream of competing in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

As a competitor, Johnson could be fiery. When he was deliberately bumped at

an indoor meeting in France, he returned the compliment so violently that

his rival crashed into the band playing in the centre of the arena— “I was

disqualified,” he said, “but it was worth it.”

Critical of the amateurish leadership of British teams in the Fifties,

Johnson helped to form the International Athletes’ Club, which did much to

improve the lot of athletes in the pre-professional era.

He became its secretary and then chairman, working well for several years

with former 10,000 metres world record holder David Bedford as they promoted

their own major international meeting.

In 1980 he encouraged British athletes to defy Margaret Thatcher’s call to

boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics because of the Soviet invasion of

Afghanistan. As passionate as ever, he described the Prime Minister as a

“fighting cock, who thought her success in the chicken run at home had

turned her feathers to armour”.

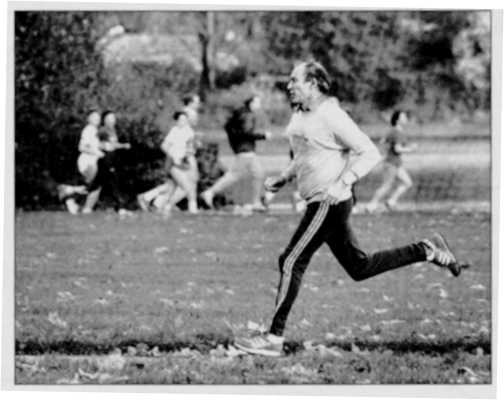

Talented, versatile and courageous: Derek Johnson training members of the

Serpentine Club in Hyde Park, London, in 1986

His final athletic challenge, when he reached 50, was to run a marathon

in 2h 55:47sec.

In recent years, Johnson battled bravely against the leukaemia which was to

cause his death on the same day that Sydney Wooderson, whose 1938 British

half-mile record Johnson had beaten back in 1955, was quietly celebrating

his own 90th birthday at home.

Johnson is survived by his second wife, Lakkhana, and their seven-year-old

daughter.

....................................................................................................................................

From The Times 15 Sept 2004

LIVES REMEMBERED

Jon Carlisle writes: I remember Derek Johnson (obituary, September 9) coming

to Bryanston in about 1958 to open our new grass running track. An 880-yards

race was staged in which he took on a relay team comprising three of the

best sprinters in the school. I think the boys just got the better of him

but it was close.

He was an inspirational, god-like figure to us 14-year-olds, and we were all

alongside him in Melbourne later that year as he vainly fought down the

finishing straight to hold off the giant American, Courtney, in that

thrilling Olympic final.

Dr James Briggs writes: I was at school with Derek Johnson in 1944-51. For

three of our first four years we were in the same class at East Ham Grammar

School. Not only was he an outstanding athlete, but he was also highly

intelligent. In a class of very bright boys he was in the first three at the

end of each term. Some of his contemporaries went on to excel in medicine,

local government and academia - not bad for a school where many of our

parents only managed to scrape along.

Copyright: The Times 2004

Not all my memories were published - the Editor cut out my

second paragraph. For the record, here's what I wrote:

"managed to scrape along - some couldn't even afford the school uniform.

After his pre clinical work at Oxford he started at the then London hospital

for his clinical work. A couple of years ago he told me that he was given

special dispensations to miss some lectures, etc in order to give him time

for athletics. He then started to become ill with what turned out to be

widespread pulmonary TB. Before this diagnosis had been made he took himself

off to the London casualty dept, hardly able to climb the stairs into the

building. When he got there he was give a roasting by the Senior Registrar

for missing so many lectures. He was also told that he only had influenza

and to go home and take some aspirin. In desperation he went to his sports

doctor at St Mary's, where his TB was rapidly diagnosed. After he had

recovered he told later me that he realised that he couldn't do both

medicine and athletics. He chose athletics. One of the last pictures taken

of him, in late February 2004, can be seen at http://mysite.freeserve.com/jcbwebsite/ehgs/DJmar04.jpg

A full history of the school he attended is at http://mysite.freeserve.com/jcbwebsite/ehgs/"

From The Ilford Recorder Thursday 9 September 2004

The athletes' champion Derek Johnson dies, 71

RECORDER SPORT's Kevin O'Connor looks back on the career of one of East

London's finest Olympians - a giant of the track.

Derek Johnson, the man regarded as Woodford Green's finest ever athlete,

died last week aged 71, after a long battle with leukaemia.

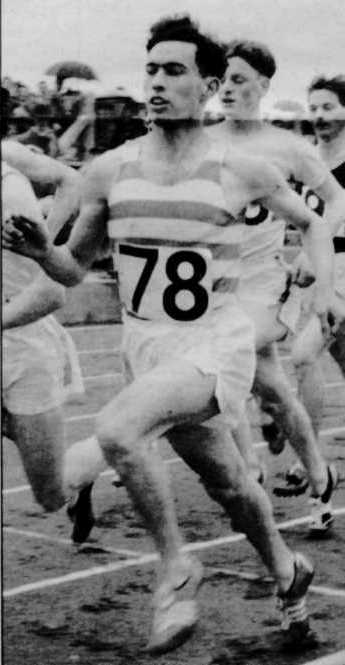

Derek Johnson, pictured in his heyday, wearing the famous hooped vest of Woodford Green AC, whom he represented for so many years, in local, national and international competitions.

A superb runner over a range of distances, his most notable achievement was

his silver medal in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, when he was beaten by the

narrowest of margins by the American Tom Courtney in the 800 metres.

But, sharp-tongued Johnson earned wider fame off the track as the creator of

the International Athletes Association.

He famously urged British athletes to ignore prime minister Margaret

Thatcher's advice to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

His stance provided significant encouragement to the likes of Daley

Thompson, Seb Coe, Steve Ovett and Allan Wells, who all won gold in Moscow.

Chigwell-born Johnson said at the time: "She (Margaret Thatcher) is a

fighting cock who thinks her success in the chicken run at home has turned

her feathers into armour."

While that outburst earned him notoriety, his words came as no surprise to

people that knew him as the angry young man of athletics.

Johnson was the scourge of officialdom in the late 1950s and clashed with

officials at Melbourne over expenses also accusing them of treating athletes

like "performing monkeys."

He was also instrumental in stopping cigarette companies from sponsoring

athletics, which came as a great source of satisfaction as he had lost his

own father to lung cancer.

Woodford president John Salisbury was also among the IAA's founders along

with London marathon founder Chris Brasher, Olympic bronze medal hurdler

John Disley and Commonwealth champion pole vaulter Geoff Elliott.

Salisbury remembers Johnson as a deeply passionate man, as well as a superb

athlete.

"I knew Derek during his competitive years as an opponent at inter-club,

county and area level and a GB team-mate in Olympic and Commonwealth Games,

as well as in European Championships and international matches, as part of

the same 4x400m relay team.

"He was a wonderful athlete and also a wonderful man to have on your side. A

great Olympian, a loyal Woodford Green club man and a great character."

Johnson first came to Woodford Green's attention when running in the annual

schools trophy meeting, single-handedly overturning Wanstead's 40m lead to

give his old school, East Ham Grammar, victory.

He blossomed at the club and went on to win several AAA and Empire Games

titles.

Despite contracting tuberculosis at the age of 30, he came back to run the

800m in 1 min 50 secs at White City to give him hope that he could make the

1964 Tokyo Olympics.

But, while he overcame TB, it was Achilles tendonitis that brought his

career to a halt as there was no cure for it in those days.

Johnson, who did his national service in Egypt, is survived by his second

wife, Lakkhana and their daughter.

Copyright: The Ilford Recorder 2004

From The Independent 15 September 2004

Olympic medallist and 'angry young man' of athletics

Derek James Neville Johnson, athlete: born Chigwell, Essex 5 January 1933;

twice married (one daughter); died London 30 August 2004.

A story told by David Bedford, his close friend and long-time ally in the

sometimes arcane world of athletics administration, says much about the

often antagonistic approach, coupled to a sharp-minded wit and willingness

to try new things, that often characterised Derek Johnson, the 1956 Olympic

800-metres silver medal-winner.

"Derek was in his late fifties, yet he agreed to travel to the European

Championships in Split on the back of my motorbike," said Bedford, the

former 10,000m world record-holder who is now the race director of the

London Marathon. By the end of the first day's travel, Johnson was windswept

and uncomfortable, and his constant complaints had annoyed Bedford. "I

warned him, one more whinge, and he'd be off," Bedford recalls, "but first

thing the next morning, Derek said, 'This is just like being in the Army.'

'That's it,' I said.

"Off you get," Bedford ordered Johnson.

"But Dave, you misunderstand me," Johnson replied, "I really loved the Army

. . ."

And Johnson really loved athletics, and he will have certainly enjoyed the

achievement of his fellow 800m runner Kelly Holmes in winning her second

Olympic gold medal in Athens less than 48 hours before his death.

Born in Chigwell, Essex, in 1933, Derek James Neville Johnson possessed a

razor-sharp mind that took him from East Ham Grammar School to medical

studies at Lincoln College, Oxford, thence to careers in computers and

property. Yet it was the abilities of Johnson's legs, heart and (eventually

TB-ravaged) lungs which earned him his greatest fame and his lifelong

passion for athletics, both on and off the track.

Johnson was a contemporary in the Oxford University Athletics Club of Roger

Bannister, organising the Iffley Road track for the first sub-four- minute

mile in 1954. Johnson went on to win that year's Empire Games 880yd title as

well as a relay gold medal. But, while his performances on the track, from

his national junior title for 440yd in 48.8sec in 1950, were notable, it was

his off-track deeds which did much to enable the likes of Kelly Holmes and

modern-day professional athletes to earn the tens of thousands of pounds

that their abilities can command.

He was dubbed an "angry young man" for his protests over athletes' derisory

daily allowance at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, and it was a tag he would

never shake off. Despite his Oxbridge background, Johnson was no fan of the

sporting establishment. A leading light in the setting up of the "athletes'

union", the International Athletes' Club, when his high-energy approach was

requested again in the 1980s as the IAC faced a financial crisis, Johnson

was then described by one of his numerous critics as the sport's "militant

tendency".

In 1980, he organised the IAC's opposition to Margaret Thatcher's call for

sportsmen to boycott the Moscow Olympics. "When she calls on the CBI to ask

its members to stop trading with the Soviet Union over Afghanistan, then

maybe we'll reconsider our position," Johnson would say. British track

athletes went to Moscow, and Allan Wells, Daley Thompson, Steve Ovett and

Sebastian Coe all won gold medals.

In the 1990s, Johnson did much of the constitutional work to set up the

British Athletic Federation and he also had a spell as secretary of the AAA,

yet his passion for competition never waned. At 50, he ran the marathon in

less than three hours and, well into his sixties, he could be seen leading a

gaggle of assorted road runners on training sessions of his own devising

around Hyde Park, taking great pride in his achievements as a coach and

mentor. Unable to race due to old running injuries, he even turned out in

Southern League matches as a hammer thrower for his club.

A proud Londoner, in June Johnson got to carry the Olympic torch as it made

its way through the capital, but, already very weak after a five-year battle

against leukaemia, he had to do so in the back of a taxi.

A bout of tuberculosis contracted on the wards when a student doctor

curtailed his international track career in 1959, causing Johnson to spend a

year in a sanatorium. Although he did not pursue the medical career, his

interest never waned: his mother had died in childbirth, his father of lung

cancer. Thus, one of Johnson's finest, and most successful, campaigns was

against tobacco sponsorship in athletics.

It is fair to say, however, that until Ovett and Coe's emergence in the

1970s, Derek Johnson was Britain's best two-lap racer since Sydney Wooderson

in the 1930s, breaking Wooderson's British record and improving it to 1:46.6

in 1957, the year after his finest performance.

Johnson missed out on Olympic gold at the Melbourne Games by a mere 0.1sec

to the American Tom Courtney, in a race which has been described as "one of

the most thrilling in Olympic annals". Johnson himself would tell that tale

of how he met Courtney in the Olympic village a couple of days after the

final.

"I've run that race a thousand times since Monday, Tom, and beat you every

time," Johnson said.

"Yeah," the American replied. "I've done that too and, Derek, I just ate you

up."

Steven Downes

Copyright The Independent 2004

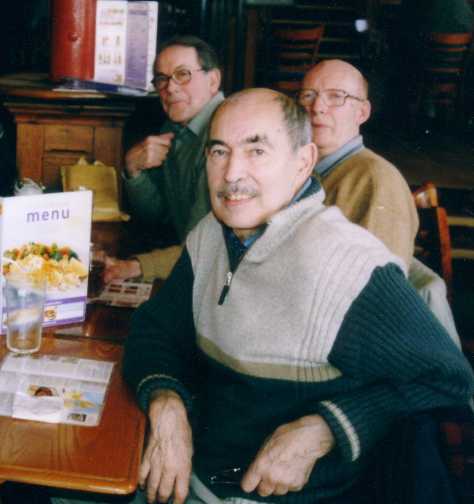

My last picture of him is at one of the regular local get-togethers with his classmates at the George in Wanstead. The picture below was taken in late February 2004 at one of these.

Jimmy Hansell behind. Bob Stapleton at rear.

Jim Briggs, former classmate.